ARFID

What is ARFID?

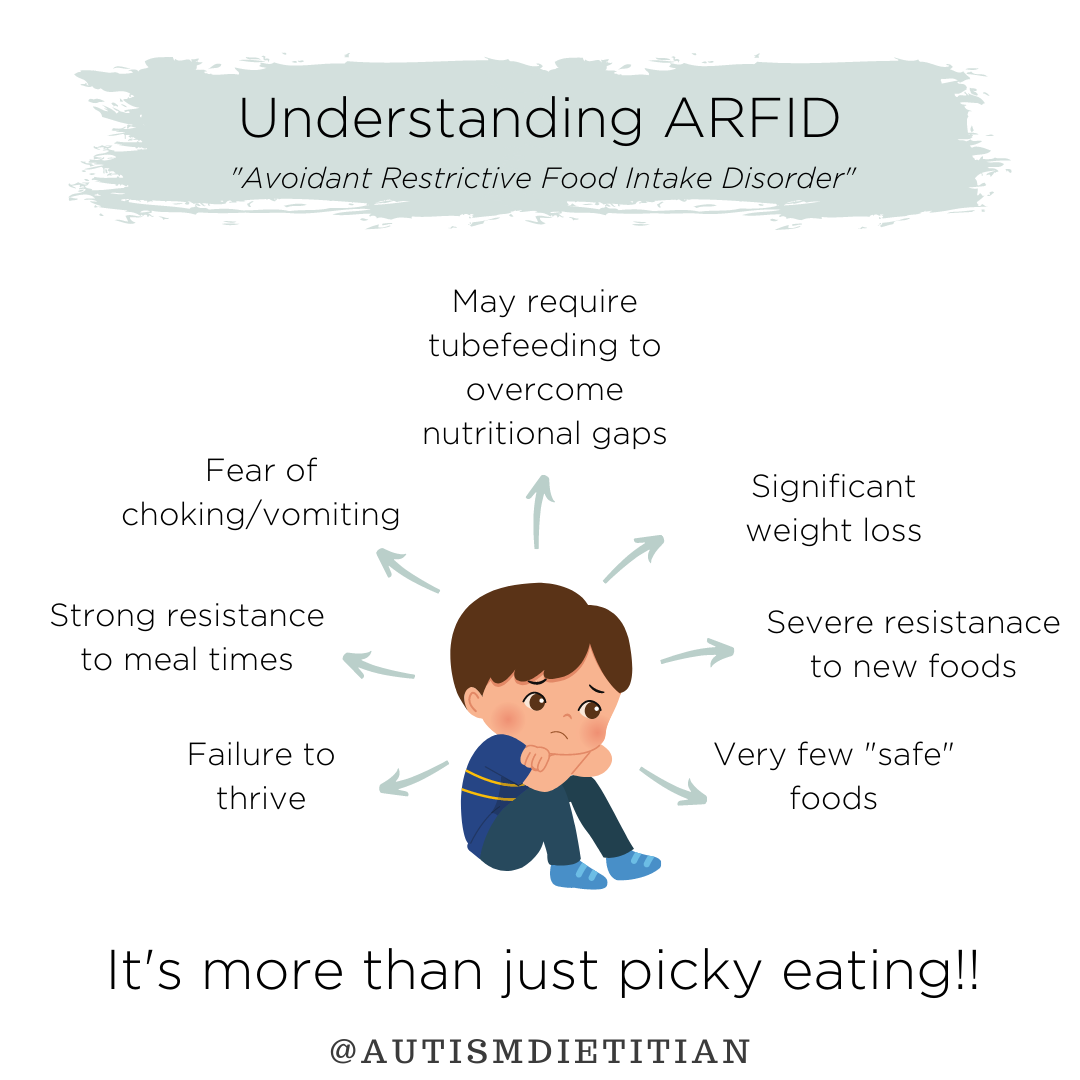

ARFID stands for Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. It is an eating disorder in which the type and amount of food is restricted and the list of accepted foods often narrows over time.

ARFID often results in poor growth, health problems, and nutrient deficiencies. This does not mean all children with ARFID are thin. In fact, one research review found that most children with autism and ARFID were not reported to be underweight.[3] If a child only eats highly processed foods, overweight or obesity may become a problem as well. [1]

ARFID is more prevalent among males, younger children (4-9 years), and children with co-morbid autism spectrum disorder (ASD). [9] It is estimated that 21% of children with autism have ARFID. [2]

ARFID can be difficult to distinguish from general picky eating. The main difference is that ARFID is more extreme. [6] A child with ARFID may avoid entire food groups, their growth and weight are often drastically impacted and they often exhibit anxiety, worry, or obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Those with ARFID also often have poor appetite or lack interest in food. [5]

It is important to note that the food avoidance/restriction associated with ARFID is not due to a lack of available food or due to cultural food practices.

Signs & Symptoms

The symptoms a doctor may use to diagnose ARFID include [5]:

Significant weight loss or faltering growth in children

Significant nutritional deficiency

Dependence on tube feeding or oral nutrition supplements

Marked interference with social situations involving food such as eating out or family meals

Physical signs/symptoms of ARFID and undernourishment [5]:

Dizziness or fainting

Fatigue

Difficulty concentrating or brain fog

Menstrual irregularities

Always feeling cold

Contributing Factors

Unlike other eating disorders, a desire to change one’s body size or shape is not the motivating factor for a person with ARFID. The motivation is typically a dislike or anxiety associated with the sensory characteristics of food including the smell, feel/texture, taste, or appearance (shape, color, etc).[5]

Many children with autism are sensory avoiders, meaning that sensory experiences are overwhelming and unpleasant for them. This often manifests as extreme picky eating, since mealtime and eating is a very sensory-rich activity. An occupational therapist can evaluate a child for sensory processing disorder.[7] Typically, consistent exposure and desensitization are the methods used to help overcome sensory overwhelm.

ARFID is also often rooted in fear as a result of traumatic past experiences. For example, if a child has vomited or choked in the past, they may be afraid it will happen again.[7] In the case of choking, the child may restrict themselves to eating only foods that are soft or pureed to avoid the risk of choking. This invites the provider or parent to ask why their child has choked. Are they able to move the food around their mouth and chew it appropriately? Are there any swallowing difficulties (dysphagia)? One study demonstrated dysphagia in 60% of patient participants.[14] Chewing and swallowing difficulties are very common among children with ASD and can be evaluated by a speech-language pathologist.

Another aspect to consider is hypotonia (low muscle tone). Hypotonia can impact a child’s ability to chew and swallow and can also affect whether or not the child has enough energy and stamina to feed themselves at mealtime. A child with low tone may struggle to support their torso while eating and quickly become fatigued. Parents can help their children by remembering the 90, 90, 90 rule. This means there should be sturdy support under the child’s feet and a 90-degree angle at the child’s ankles, support from a chair under the legs, with a 90-degree angle at the knees, and support at the sides of the child/around their torso with a 90-degree angle at hips.

Another potential root cause of ARFID may be pain.[7] If a child has pain after eating (as a result of GERD for example), they may associate eating with pain and show little interest in food. Pain can also stem from a food sensitivity that causes gastrointestinal upset. Using a food sensitivity test like the Mediator Release Test (MRT) can be helpful in determining what if any foods may be causing pain.

Next Steps

Diet

Consult with your current Speech Language Pathologist and/or Occupational Therapist about adding feeding to your child’s goals and treatment plan. FeedingMatters.org has a large collection of resources and therapists to support kids with Pediatric Feeding Disorder and ARFID.

Consider finding an SOS Feeding Therapist in your area to work on increasing food repertoire

Research indicates that those with ARFID often do not consume enough of the following nutrients [3,4,8]:

These should be screened for by a dietitian to determine if any true deficiencies exist, so they can be corrected or prevented with supplementation and/or targeted feeding therapy.

Nutrient deficiency can manifest as fatigue, brain fog, thinning hair, brittle nails, mouth sores & cracks, eczema, low muscle tone, fragile bones, poor sleep, vision loss, and many other serious symptoms.

Chronic Constipation

Diets of selective eaters tend to consist of foods that are extremely low in fiber, such as processed and refined grains, microwavable meals, packaged snacks, and fried foods.

Without fiber, the GI system is not able to function properly, and can become backed up and “stuck”. Constipation is a very common issue in autism.

Constipation can be managed with diet! Check out the Constipation note for more information.

If your child has GI problems other than constipation, check out the Gastrointestinal Issues note.

Supplements

Appropriate supplements will differ depending on what nutrients a person needs. Some children may be low in macronutrients like protein, fat, or fiber while others aren’t getting enough micronutrients like vitamins and minerals. A dietitian that specializes in autism or picky eating support can help parents find quality supplements that meet nutrient needs.

Nutrient levels should be monitored regularly for those with ARFID in order to catch any deficiencies early and to inform the use of supplements to assist in replenishing nutrient levels and preventing further depletion.

Consider various supplements to help fill the gaps in your child’s nutrient needs, such as:

Lifestyle

One thing that can help build a child’s appetite is routine when it comes to meals and snacks. Structure is encouraged, with 3 meals and 1 or 2 snacks each day, typically around the same time and in the same place. [15]

Avoid pressuring your child to eat or take bites, as this can actually worsen picky eating - this includes bribing with rewards of preferred foods. [11, 15] Mealtime should be calm and non-stressful. A child will feel more comfortable and inclined to explore if there is no pressure to eat something they aren’t ready for.

Consistent exposure to foods, especially non-preferred foods is critical in the effort to help a child eat a more varied diet. [12, 15] Be sure to regularly offer new foods. If the child doesn’t want the new food on their plate, use a separate plate for learning about or exploring new foods.

Engaging a child in all the steps that happen before the food gets to the table is a nice way to increase exposure to foods. Parents or caregivers can involve the child in gardening, grocery shopping, and preparing/cooking the meal.

The old saying “don’t play with your food” does not apply when it comes to picky eaters and ARFID. Playing with food is essential! This is how children learn about food, what it feels like, looks like, how it moves, how it smells, etc. Playing with food and becoming more familiar with each one is how children become less fearful and hesitant of new foods.

Structured feeding therapy sessions with therapists trained in the SOS Approach to Feeding are a great option for helping children expand their diet.

There is no standardized approach to treatment for ARFID. The options for treatment thus far include parent training/family-based approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy with a mental health professional, intensive in-patient programs often offered at hospitals, and medications designed to increase appetite. [13]

DISCLAIMER: Before starting any supplement or medication, always consult with your healthcare provider to ensure it is a good fit for your child. Dosage can vary based on age, weight, gender, and current diet.

ARFID & Autism in the Research

Prevalence of ARFID

ARFID is highly co-morbid with autism, with a prevalence of 21% in this large cohort. [2]

Genetics & ARFID

Estimates indicate that up to 17% of parents of autistic children are also at heightened risk for ARFID, suggesting a lifelong risk for disordered eating. [2]

Nutrition & ARFID

A research review found that nutritional deficiencies related to inadequate intakes of vitamin A, thiamin (B1), vitamin B-12, vitamin C, and vitamin D were found in individuals with autism and ARFID. [3]

Another study found that those with ARFID had significantly reduced protein and total caloric intake (compared with controls). Those with ARFID met only 20–30% of the recommended intake for most vitamins and minerals, with a significantly lower intake of vitamins B1, B2, C, and K and minerals including zinc, iron, and potassium. Those with ARFID also have much less variety in their diet for all food groups, except carbohydrates. [4]

Another study reported that among children that had ASD and severe food selectivity, caregivers reported 67% of the sample omitted vegetables and 27% omitted fruits. Seventy-eight percent consumed a diet at risk for five or more inadequacies. Risk for specific inadequacies included vitamin D, fiber, vitamin E, and calcium. [8]

ARFID Treatment

Clinicians rated 17 patients (85%) as "much improved" or "very much improved." ARFID severity scores significantly decreased per both patient and parent reports. Patients incorporated an average of 16.7 new foods from pre- to post-treatment. The underweight subgroup showed a significant weight gain of 11.5 pounds, At post-treatment, 70% of patients no longer met the criteria for ARFID. [10]

-

[1] Zucker N. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). In: Encyclopedia of Feeding and Eating Disorders. Springer Singapore; 2016:1-4.

[2] Koomar T, Thomas TR, Pottschmidt NR, Lutter M, Michaelson JJ. Estimating the Prevalence and Genetic Risk Mechanisms of ARFID in a Large Autism Cohort. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:668297.

[3] Yule S, Wanik J, Holm EM, et al. Nutritional Deficiency Disease Secondary to ARFID Symptoms Associated with Autism and the Broad Autism Phenotype: A Qualitative Systematic Review of Case Reports and Case Series. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121(3):467-92.

[4] Schmidt R, Hiemisch A, Kiess W, von Klitzing K, Schlensog-Schuster F, Hilbert A. Macro- and Micronutrient Intake in Children with Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):400.

[5] Ellis E. When Picky Turns Problematic: What to know about ARFID. Food & Nutrition Magazine. Published June 21, 2021. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://foodandnutrition.org/from-the-magazine/when-picky-turns-problematic-what-to-know-about-arfid/

[6] Dovey TM, Kumari V, Blissett J. Eating behaviour, behavioural problems and sensory profiles of children with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), autistic spectrum disorders or picky eating: Same or different. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;61:56-62.

7 De Toro V, Aedo K, Urrejola P. [Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID): What the pediatrician should know]. Andes Pediatr. 2021;92(2):298-307.

[8] Sharp WG, Postorino V, McCracken CE, et al. Dietary Intake, Nutrient Status, and Growth Parameters in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Severe Food Selectivity: An Electronic Medical Record Review. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(10):1943-50.

[9] Farag F, Sims A, Strudwick K, et al. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and autism spectrum disorder: clinical implications for assessment and management. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64(2):176-82.

[10] Thomas JJ, Becker KR, Kuhnle MC, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Feasibility, acceptability, and proof-of-concept for children and adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(10):1636-46.

[11] Fries LR, van der Horst K. Parental Feeding Practices and Associations with Children's Food Acceptance and Picky Eating. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2019;91:31-9.

[12] Patel MD, Donovan SM, Lee SY. Considering Nature and Nurture in the Etiology and Prevention of Picky Eating: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):E3409.

[13] Thomas JJ, Wons OB, Eddy KT. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(6):425-30.

[14] Leader G, Tuohy E, Chen JL, Mannion A, Gilroy SP. Feeding Problems, Gastrointestinal Symptoms, Challenging Behavior and Sensory Issues in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(4):1401-10.

[15] Patel MD, Donovan SM, Lee SY. Considering Nature and Nurture in the Etiology and Prevention of Picky Eating: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):E3409.